Why the Democratic Path to 270 Electoral Votes Is Growing Narrower

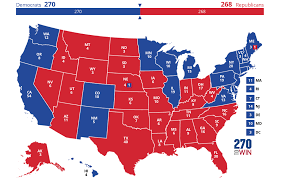

For much of modern American politics, Democratic presidential victories have rested on a dependable and familiar group of states. Large, reliably Democratic states such as California, New York, and Illinois have long formed the backbone of the party’s Electoral College strategy. When paired with support from parts of the industrial Midwest—especially Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania—this coalition has repeatedly enabled Democratic nominees to reach or exceed the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency. For decades, this formula provided Democrats with a relatively stable and flexible path to the White House.

Since the early 1990s, Democratic campaigns have leaned heavily on this same core of populous, urban-centered states. Characterized by large metropolitan areas, diverse populations, and strong labor traditions, these states offered a dependable base that allowed Democrats to focus their resources on a limited number of competitive battlegrounds. This approach proved effective across multiple election cycles and shaped how the party organized nationally.

However, a growing number of political analysts now argue that this long-standing strategy may be nearing a breaking point. By the early 2030s—particularly in the 2032 presidential election—the Democratic electoral map could become significantly tighter than it has been in recent decades. Shifts in population growth, domestic migration, and congressional apportionment are reshaping the Electoral College in ways that could shrink Democrats’ margin for error. What was once a broad pathway to victory may evolve into a narrower, more fragile route.

At the heart of this transformation is the changing distribution of the U.S. population. Over recent decades, Americans have steadily moved away from traditional population centers in the Northeast and Midwest toward the South and Southwest. States that have historically anchored Democratic victories—most notably California, New York, and Illinois—have seen slower population growth and, in some cases, outright declines. While these states remain influential economically and culturally, their share of the national population is no longer growing at the pace it once did.

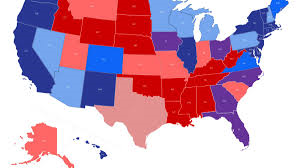

Domestic migration is a key driver of this trend. Rising housing costs, higher taxes, congestion, and affordability challenges have pushed millions of residents to relocate in search of better economic opportunities and lower living expenses. States such as Texas, Florida, Arizona, North Carolina, and South Carolina have absorbed much of this growth, benefiting from expanding job markets, lower costs of living, and favorable climates.

Every decade, the U.S. Census triggers a reapportionment of congressional seats based on population changes. Because a state’s electoral votes are tied directly to its representation in Congress, population losses result in reduced Electoral College influence, while population gains increase it. As slower-growing states lose seats in the House, their electoral power declines. Even small reductions—one or two electoral votes per state—can add up quickly when multiple Democratic-leaning states experience losses at the same time.

Over time, this erosion means Democrats begin each election cycle with fewer reliable electoral votes than they once could count on. At the same time, rapidly growing states are projected to gain additional congressional seats and electoral votes. Many of these states lean Republican or remain highly competitive rather than safely Democratic. Texas and Florida, for instance, have already expanded their Electoral College influence significantly. Although Democrats have made gains in certain urban and suburban areas within these states, winning statewide presidential contests there remains difficult.

This shift creates a built-in structural challenge. As electoral votes migrate away from Democratic strongholds and toward states where Republicans perform well or enjoy institutional advantages, the GOP gains a head start before campaigns even begin. While this does not guarantee Republican victories, it raises the bar Democrats must clear to win national elections.

Compounding the issue is the evolving political landscape of the Midwest. States such as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania were once dependable Democratic allies, anchored by manufacturing economies and strong union memberships. Economic changes, industrial decline, and cultural polarization have since transformed these states into true battlegrounds. Recent elections have shown that even small changes in turnout or voter preferences can swing outcomes.

As a result, simply holding the traditional Midwestern “blue wall” may no longer be enough. Even if Democrats win those states, the reduced number of electoral votes elsewhere may still leave them short of 270. This reality could force the party to expand its map by winning states that have historically leaned Republican, such as Arizona, Georgia, or North Carolina—each of which adds cost, complexity, and uncertainty to presidential campaigns.

Redistricting trends further complicate the picture. After each census, state legislatures redraw congressional maps, shaping political power at the state level. In states controlled by Republicans, redistricting has often reinforced GOP advantages. While redistricting does not directly affect presidential vote totals, it influences party organization, voter engagement, and turnout, indirectly shaping national outcomes.

Taken together, these forces suggest that Democrats may enter the 2030s with a more constrained Electoral College path than at any time in recent history. The party’s traditional reliance on a small group of large states may no longer provide sufficient insulation against losses elsewhere. To remain competitive, Democrats may need sustained investments in voter outreach, organizing, and coalition-building in fast-growing states where population gains are reshaping political dynamics.

At the same time, demographic change does not automatically translate into predictable political outcomes. States gaining population are not politically fixed. Urban growth, generational turnover, and increasing racial and ethnic diversity can gradually shift voting patterns, as seen in places like Arizona and Georgia. Still, demographic evolution alone may not fully counterbalance the structural advantages Republicans gain from population redistribution and the geographic concentration of Democratic voters in urban areas.

Looking ahead, the 2032 election could serve as a crucial test of the Democratic electoral strategy. If current trends continue, Democrats may begin that cycle with fewer guaranteed electoral votes and greater dependence on winning multiple competitive states simultaneously. This increases vulnerability to economic shocks, international crises, or shifts in public opinion that could tip close races.

Meanwhile, Republicans may benefit from a broader and more forgiving electoral map. Population growth in Republican-leaning states, combined with strong support in rural and exurban regions, could allow GOP candidates to remain competitive even when losing the national popular vote. This dynamic highlights the growing tension between demographic realities and Electoral College outcomes.

Ultimately, the evolving electoral landscape reflects deeper societal changes—where Americans live, how they work, and what they value. For Democrats, adapting to this environment may require more than tactical campaign changes. It could demand a fundamental rethinking of coalition-building, geographic outreach, and policy priorities. While no election outcome is predetermined, the warning signs are clear: the Democratic path to the presidency, once broad and resilient, may soon depend on a narrower and more delicate balance of states, where every electoral vote carries greater weight than ever before.