Everyone Knows Her as Obama’s Mother — Few Know the World She Changed

Most people recognize her name only because of her son. But long before Barack Obama became president, Ann Dunham had already lived an extraordinary life—one that quietly changed how the world understands poverty.

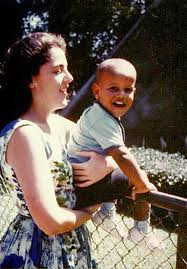

In 1960, Stanley Ann Dunham—known simply as Ann—was an 18-year-old student at the University of Hawaii when she met Barack Obama Sr., a confident and intellectually driven economics student from Kenya. Their relationship moved quickly. Ann became pregnant, they married, and she gave birth to a son at an age when most young women were still discovering who they were.

In that era, the script was predictable. A young mother, an early marriage, ambitions set aside. For many women in 1960, that was the end of the story.

For Ann, it was only the beginning.

The marriage soon fell apart. Obama Sr. left to continue his studies at Harvard and later returned to Kenya, leaving Ann to raise her son alone. But she refused to stop learning or surrender her ambitions. She continued her education, balancing coursework with motherhood, determined to build a life defined by more than circumstance.

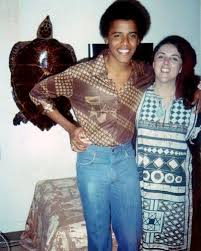

In 1965, Ann remarried Lolo Soetoro, an Indonesian graduate student. Two years later, the family moved to Jakarta, bringing six-year-old Barack with them. Indonesia was worlds apart from Hawaii—poor, overcrowded, and still reeling from political turmoil. Many Americans in her position stayed within expatriate enclaves, shielded from local hardship.

Ann chose the opposite path.

She learned the language, immersed herself in daily life, and became deeply engaged with Indonesian communities. She didn’t view poverty as an abstract concept or a cultural curiosity. She studied it with discipline and purpose, asking hard questions about why hardworking people remained poor despite their skills.

Her research focused on rural blacksmiths—not as quaint artisans, but as participants in an economic system stacked against them. She traveled to remote villages, documenting how craftspeople sourced materials, sold goods, and struggled under barriers they couldn’t control. While many development experts of the time blamed poverty on tradition or lack of motivation, Ann reached a different conclusion.

The problem wasn’t culture. It was access.

Rural workers had talent and drive, but no credit, no savings systems, and no reliable markets. That insight became the cornerstone of her life’s work.

While raising two children—her daughter Maya was born in 1970—Ann enrolled in graduate school at the University of Hawaii, commuting between Honolulu and Jakarta. She completed her master’s degree while conducting extensive fieldwork, juggling academia, family, and international travel.

And she didn’t stop at research.

Through organizations like USAID and the Ford Foundation, Ann helped design early microfinance programs that gave small loans and savings opportunities to rural women. These initiatives weren’t charity—they were structured credit systems based on trust and economic dignity. Women used the loans to expand businesses, stabilize income, and support their families.

The results were transformative. The village-level credit models Ann helped develop became templates for microfinance efforts around the world—years before the concept gained global recognition or a Nobel Prize.

Colleagues described her as far ahead of her time. She wasn’t vocal about feminism in speeches, but she embodied it in action—insisting on intellectual seriousness, pursuing a doctorate while raising children across continents, and refusing to be dismissed as “just a mother.”

In 1992, Ann completed her Ph.D.—a massive 1,043-page dissertation on Indonesian peasant blacksmithing that combined ethnography with rigorous economic analysis. It demonstrated that traditional crafts could thrive when supported by fair systems and access to resources.

But by then, her health was failing.

In late 1994, Ann was diagnosed with advanced ovarian and uterine cancer. She had ignored symptoms for months, too focused on her work and responsibilities. On November 7, 1995, she died at just 52 years old.

Her son was 34, working as a lawyer and community organizer in Chicago. He had not yet run for the U.S. Senate. The presidency was still more than a decade away.

Ann never saw her son rise to national office. Never watched a campaign. Never witnessed an inauguration. She died believing she had lived a meaningful but modest life—one devoted to scholarship, service, and raising two children.

She never knew that her name would one day be spoken by millions.

When Barack Obama later spoke of his mother, he pointed to the values she instilled: education, empathy, dignity, and belief in ordinary people. Those values echoed through his policies—from healthcare to education to women’s economic empowerment.

Yet Ann Dunham’s legacy stands on its own.

She helped pioneer microfinance systems still used worldwide. She reshaped how poverty is understood, showing it stems from structural barriers, not personal failure. She proved that small, thoughtful interventions can unlock human potential.

Everyone may know her as Obama’s mother.

But Ann Dunham was a groundbreaking anthropologist, a quiet innovator, and a woman who changed lives—long before the world was watching.