When $5 a Day Changed the Working Class Forever

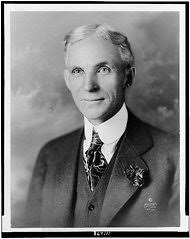

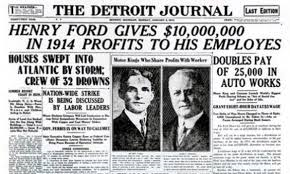

On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford made one of the most shocking and consequential announcements in American industrial history. The founder of the Ford Motor Company declared that his factory workers would earn $5 a day—more than double the prevailing industrial wage at the time. Overnight, Ford upended the economic assumptions of the early 20th-century workplace and set off a wave of disbelief, admiration, and controversy across the nation.

At a time when most factory laborers earned roughly $2 to $2.50 for grueling, repetitive work, Ford’s decision seemed almost reckless. Newspapers questioned whether the company could survive such generosity. Rival industrialists accused him of grandstanding or trying to destabilize labor markets. Economists were baffled. But Ford had a calculation in mind—one rooted not just in profit, but in control.

Why Ford Raised Wages

Ford’s factories were facing a serious problem: worker turnover. Assembly-line labor was monotonous, exhausting, and mentally draining. In 1913 alone, Ford Motor Company experienced turnover rates as high as 370%, meaning the company had to hire and train more than three workers to keep one position filled. Productivity suffered, costs soared, and morale was low.

Ford believed higher wages would solve this. By paying workers enough to live comfortably—and even afford the cars they built—he hoped to stabilize his workforce, increase efficiency, and reduce costly retraining. In this sense, the $5 day was both a humanitarian gesture and a shrewd business strategy.

But there was a catch.

The Price of Prosperity

The extra pay wasn’t automatic. To qualify for the full $5 daily wage, workers had to meet strict behavioral standards enforced by Ford’s Sociological Department—a group of 53 investigators tasked with monitoring employees’ private lives.

These investigators conducted unannounced home visits, inspecting living conditions and questioning workers and their families. They looked for signs of what Ford considered “moral behavior.” Alcohol use, gambling, unsanitary housing, debt, and even certain personal relationships could disqualify a worker from receiving the higher wage.

Ford believed that stable family life, sobriety, and thrift produced better workers. Critics, however, saw this as an invasive form of corporate paternalism—an employer policing not just labor, but lifestyle.

Immediate Impact

Despite the controversy, the results were undeniable. Worker turnover plummeted almost overnight—from hundreds of percent to nearly zero. Productivity soared. Absenteeism dropped. Workers stayed.

Thousands of men flooded Detroit, hoping to land a job at Ford. Lines formed outside factories. For many families, the $5 day meant better housing, improved health, and opportunities that had previously been out of reach.

For the first time, industrial wages supported something resembling a middle-class life.

A New Economic Model

Ford’s decision rippled far beyond his own factories. Other companies, though initially resistant, were eventually pressured to raise wages to compete for labor. Economists began to reconsider the idea that low wages were necessary for profitability.

Ford also helped redefine the relationship between labor and consumption. By paying workers enough to buy the products they made, he created a self-reinforcing economic cycle that would become a foundation of modern capitalism.

A Complicated Legacy

The $5 day is remembered today as both visionary and deeply flawed. It helped lift thousands of working families out of poverty and demonstrated that higher wages could coexist with massive corporate success. At the same time, Ford’s moral surveillance blurred the line between employer and authority figure, raising lasting questions about privacy and power.

Still, history has rendered its verdict on the outcome.

High wages combined with strict rules transformed Ford’s workforce, stabilized production, and played a key role in the emergence of the American middle class. What began as a radical experiment became a turning point in labor history—proof that economic progress could be built not only on efficiency, but on paying workers enough to live with dignity.

On that winter day in 1914, Henry Ford didn’t just change wages.

He changed expectations.