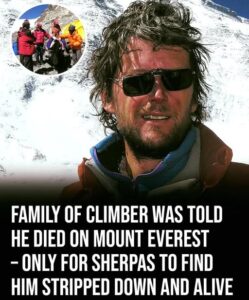

Left for Dead on Everest — The Miraculous Survival of Lincoln Hall (Expanded retelling)

High on Mount Everest, where the air is thin enough to steal your breath and the wind strips language from your lips, ordinary rules no longer apply. In late May 2006, Australian climber Lincoln Hall learned that lesson the hardest way possible — and then, impossibly, taught the world something new about survival, compassion, and the unpredictable mercy of the mountain.

This is the fuller story of how a man assumed dead came back to life on the world’s highest ridge, how strangers chose humanity over glory, and how one extraordinary night changed the course of many lives.

The approach: preparation, risk, and the death zone

Everest asks everything of the people who go after it. Climbers train for years — building stamina, learning rope systems, and rehearsing the cold logic of high-altitude decision-making — but the mountain remains indifferent to years of preparation. Above roughly 8,000 meters, in the so-called “death zone,” the human body cannot acclimatize: every breath steals oxygen the body needs to sustain itself, cognitive function blurs, and judgment can collapse like a tent in a gale.

Lincoln Hall was no novice. He had summited other big peaks and knew the hazards. Yet, despite experience and training, something went terribly wrong near the summit in 2006. Hall developed high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), a swelling of the brain triggered by extreme altitude. He became confused, disoriented, and began to hallucinate — the textbook progression toward unconsciousness and, if untreated, death.

An impossible decision

When a climber collapses in the death zone, every second counts — and every choice carries a moral and practical weight. Hall’s Sherpa team and expedition mates fought to keep him going: they tried to move him, to shelter him, to oxygenate him. But a storm closed in, the night was descending, and oxygen supplies were critically low. In that context, with increasing risk to the lives of those still able to descend, the Sherpas and expedition leaders faced a gut-wrenching calculus. After hours of struggle, the team reported Hall had stopped breathing and, believing him dead, left his body on the ridge.

News of Lincoln’s death reached back to Australia. Family and friends mourned. The tragic headlines — another life claimed on Everest — were easy to write. What no one expected was that the story had not reached its final chapter.

Alone on the ridge — and still alive

Alone, exposed, stripped of most of his gear, Lincoln somehow regained consciousness in the blackout hours of the night. He awoke in a thin fleece jacket with no gloves, hat, goggles, or oxygen, perched beside a dizzying drop with the mountain’s wind slicing at him. The conditions were uniformly fatal by every rational standard: extreme cold, no protection from the gale, and severe altitude sickness. Yet against all odds he survived through the night.

What kept him alive is still debated — a mixture of physiological quirks, hardened endurance, and perhaps the random luck of where he lay and how his body reacted. Whatever the reasons, dawn found him alive and alone on the ridge.

A chance encounter and a moral choice

As daylight spread, another summit team crested the horizon. Led by American climber Dan Mazur, with teammates Myles Osborne, Andrew Brash, and Jangbu Sherpa, they first glimpsed what looked like another body — a common, grim sight on Everest. But as they closed the distance, they saw the impossible: the figure was upright and breathing.

Lincoln looked at them and reportedly said, calmly and with a touch of bewilderment, “I imagine you’re surprised to see me here.”

That sentence crystallized the moment. The rescuers were on a summit push — the culmination of months or years of preparation and a once-in-a-lifetime chance for many on the team. Turning back would almost certainly cost their summit bid. Continuing would be a direct condemnation of a living person.

Mazur later recalled the decision as instant and unequivocal: they would help. The team abandoned their summit attempt and knelt to the work of stabilization — oxygen, warm clothing, food, water. They radioed for assistance, understanding fully that the logistics of a rescue at that altitude were brutal. Still they stayed, refusing to leave someone who was alive.

Rescue and recovery

Hours of hard, exposed effort followed. Rescue Sherpas climbed from lower camps, an emergency operation coalesced, and Hall was eventually assisted down to the North Col and then to Advanced Base Camp. There, medical personnel treated him for frostbite, dehydration, and the brain swelling that nearly killed him.

Hall survived, albeit with permanent frostbite damage to the tips of some fingers and a toe. The climbing community reacted with astonishment and admiration. Stories of climbers left for dead are tragically common on Everest; stories of a resurrection are not.

Aftermath: gratitude, controversy, meaning

Lincoln Hall emerged from the ordeal without spite. He understood the impossible choice the Sherpas had faced — leaving a patient believed dead in order to preserve the lives of those who could still descend. Instead of blaming, he thanked the team that came back for him. He later wrote about his experience in Dead Lucky: Life After Death on Mount Everest, reflecting on the brush with death and the spiritual and philosophical changes that followed. Tibetan Buddhist ideas and a sense of renewed purpose informed much of his thinking after the climb.

Dan Mazur and his team were widely lauded for their decision. “You can always go back to the summit. But you only have one life to live,” Mazur said, words that captured the moral heart of the episode and resonated across mountaineering and mainstream audiences alike. National Geographic and numerous media outlets honored their courage and ethical clarity.

At the same time, the episode sparked debate within the climbing world about the practical limits of rescue at extreme altitude, the ethical responsibilities of teams, and the unavoidable trade-offs between personal ambition and human life. The Sherpas who initially left Hall faced public scrutiny, even as many in the community defended their decision as a grim but necessary action in a lethal environment.

Lincoln’s later years and legacy

Lincoln Hall lived six more years after his Everest miracle. He traveled, wrote, spoke about the experience, and devoted energy to causes he cared about. In 2012, Hall died at age 56 from mesothelioma, a cancer linked to past asbestos exposure from his early working life — a tragic, unrelated end to a man who had once defied death on a mountain.

He left a wife and two sons, and a legacy that continues to be told to climbers, rescue workers, and anyone who wonders how humanity behaves when faced with impossible choices. His story is told as a lesson in humility and in the value of choosing life over laurels.

What the mountain taught us

Lincoln Hall’s survival remains one of mountaineering’s most remarkable episodes because it bundles together adversity, human error, mercy, and moral courage. It forces us to reckon with the thin line between survival and loss, and with how strangers can become saviors when they decide that a person’s life matters more than their personal ambition.

On Everest, the summit is never guaranteed. But the Hall rescue reminds us that, sometimes, the greater ascent is the decision to turn back — to save a life rather than claim a peak. That lesson, echoing from a narrow ridge above 8,000 meters, is why the story endures: because in the coldest, most indifferent places, it is still possible for people to risk everything to help one another.