Can You Spot the Squares? Most People Get This Wrong

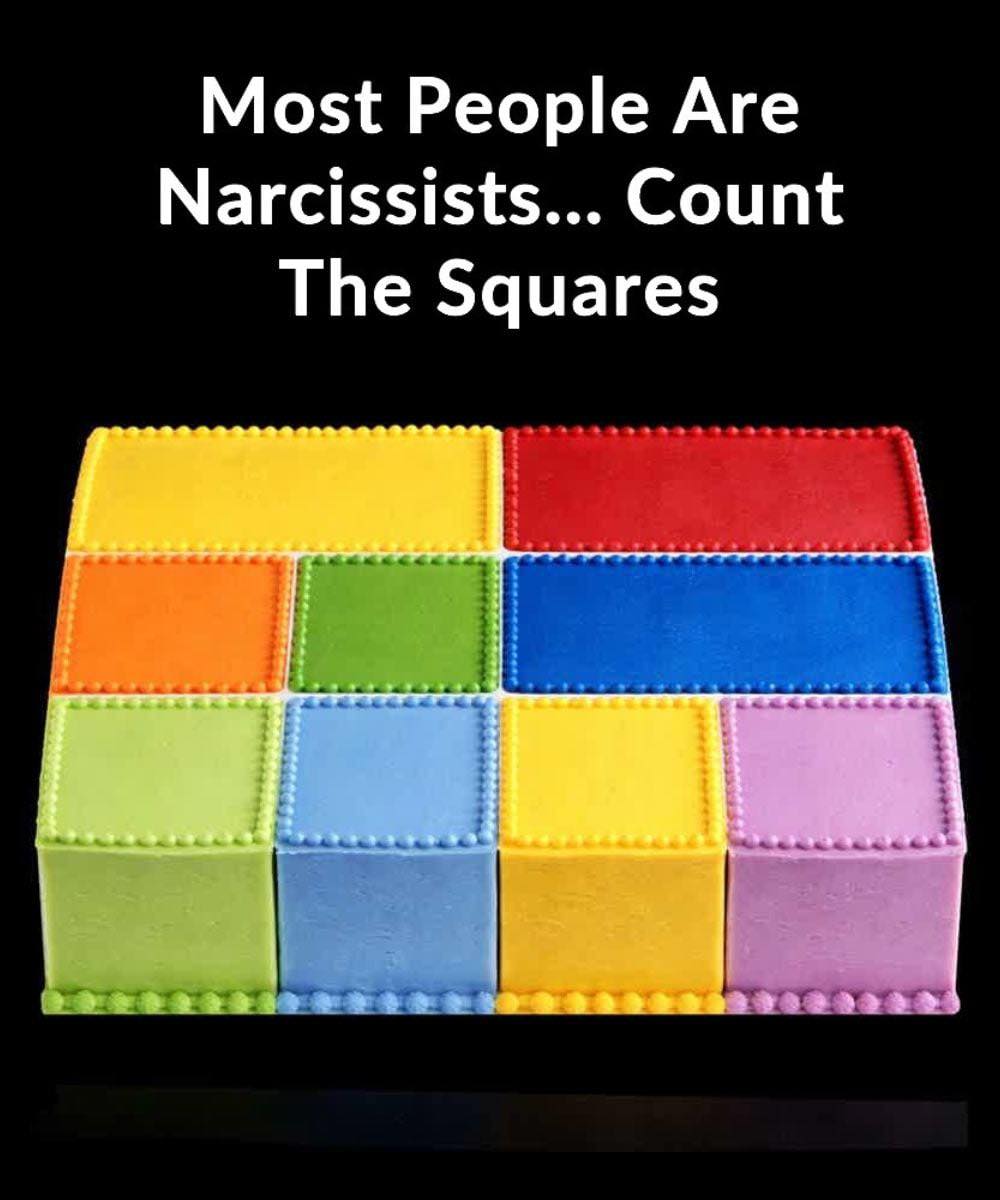

Most People Are Narcissists… Count the Squares

There’s a deceptively simple puzzle that circulates online and in classrooms: a grid of intersecting lines forming multiple squares. The question is straightforward:

“How many squares do you see?”

Most people answer quickly. Sixteen. Maybe twenty. A few more careful observers say thirty. Someone insists there are forty.

And suddenly, what looked like a harmless visual game becomes a subtle psychological experiment.

Because the puzzle is not really about squares.

It’s about certainty.

It’s about ego.

It’s about how tightly we cling to our perspective.

And that’s where the uncomfortable idea comes in:

Most people are narcissists.

Not in the clinical sense. Not in the exaggerated caricature of vanity and grandiosity. But in a quieter, more pervasive way — the everyday narcissism of believing our perception is complete.

Let’s count the squares.

The First Count: The Obvious Squares

When you first look at the grid, your brain identifies the most prominent shapes — the largest squares. They stand out clearly. Your visual system is wired to detect simple, high-contrast patterns.

You count them confidently.

Then maybe you notice the smaller squares inside. You adjust your answer.

What you probably don’t notice immediately are the composite squares — the ones formed by combining smaller sections. The shapes that exist, but aren’t immediately visible because your brain favors simplicity over complexity.

This is how perception works.

The brain is not a camera. It is a prediction engine. It fills gaps, prioritizes efficiency, and settles for “good enough” rather than exhaustive accuracy.

The result?

We mistake quick perception for full understanding.

And we do the same thing in life.

Everyday Narcissism: The Certainty Reflex

When someone gives a different answer to the square puzzle, what’s your first reaction?

Curiosity?

Or correction?

Most people instinctively defend their number. They recount quickly, not to discover new squares — but to confirm their original answer.

This is the certainty reflex.

We don’t just want to see.

We want to be right.

That subtle attachment to correctness is a form of everyday narcissism — a cognitive bias where our perspective becomes central, privileged, and protected.

It shows up in phrases like:

- “It’s obvious.”

- “I know what I saw.”

- “That’s not what happened.”

- “You’re overthinking it.”

These statements aren’t malicious. They’re protective.

Being wrong threatens identity.

Being uncertain feels destabilizing.

So we cling.

Not the Disorder — The Default

Let’s be clear: narcissistic personality disorder is a serious clinical condition. It involves deep patterns of grandiosity, lack of empathy, and need for admiration.

But what we’re exploring here is different.

It’s the baseline human tendency to:

- Assume our perception is accurate.

- Prioritize our interpretation.

- Resist challenges to our viewpoint.

- Overestimate our objectivity.

This isn’t pathology.

It’s wiring.

The square puzzle simply exposes it in a safe, low-stakes way.

If we can be so certain — and so wrong — about counting shapes, what does that say about how we navigate relationships, politics, or morality?

The Overconfidence Illusion

Psychologists have long documented the overconfidence effect — our tendency to overestimate the accuracy of our judgments.

In experiments, people consistently rate their answers as more accurate than they actually are. This is especially true when tasks feel easy.

The square puzzle feels easy.

That’s why it works.

The more obvious something appears, the more confident we become.

But obvious is not the same as complete.

Confidence is not the same as correctness.

And certainty is not the same as truth.

Arguments Are Just Square Puzzles

Consider a disagreement between two people.

Each person recounts the same event differently.

Each insists their memory is clear.

Each feels justified.

From the inside, their perception feels as concrete as counting visible squares.

But memory is reconstructive. It’s shaped by emotion, bias, and narrative framing. Just like visual perception, it fills in gaps.

In arguments, we rarely assume we missed something.

We assume the other person did.

That assumption — “My grid is accurate; yours is flawed” — is everyday narcissism in action.

Social Media: Competitive Square Counting

In the digital age, square counting has become performative.

Social media rewards certainty. Bold statements travel faster than nuanced ones. The algorithm favors confidence over contemplation.

People announce their “square counts” loudly:

- Political takes

- Moral judgments

- Social critiques

- Cultural interpretations

Rarely do we see posts that say:

“I might be missing something.”

“I could be wrong.”

“Let’s count this together.”

Instead, we see declarations.

Certainty becomes identity.

And identity becomes territory to defend.

The grid grows more complex — but our willingness to recount shrinks.

The Fear Beneath Narcissism

Narcissism isn’t born from strength.

It’s born from vulnerability.

When someone challenges your square count, something subtle happens inside:

A tightening in the chest.

A rush to justify.

An impulse to defend.

Why?

Because being wrong — even about something trivial — threatens competence. It whispers:

Maybe you overlooked something obvious.

Maybe you’re not as perceptive as you thought.

Maybe your confidence was misplaced.

The ego reacts to that whisper like a threat.

So it doubles down.

“It’s definitely sixteen.”

And the conversation ends.

Hidden Squares in the Self

The most important grid isn’t external.

It’s internal.

We count our obvious traits:

- I’m responsible.

- I’m logical.

- I’m kind.

- I’m strong.

But we often overlook the composite squares — the hidden motivations and fears formed by overlapping experiences.

- The need for approval beneath kindness.

- The fear of failure beneath ambition.

- The insecurity beneath perfectionism.

- The anger beneath sarcasm.

When someone points out these hidden squares, we resist.

“That’s not why I did that.”

“You’re reading into it.”

“I’m not like that.”

But perhaps there are more squares than we initially counted.

The Narcissism of Good Intentions

One of the most subtle forms of narcissism is the belief that good intentions guarantee correct perception.

We assume:

If I mean well, I must see clearly.

But intention does not eliminate bias.

We can care deeply and still miscount.

We can act sincerely and still overlook hidden shapes.

Humility requires accepting that goodness does not equal omniscience.

The Discipline of Recounting

What if disagreements became invitations rather than battles?

Instead of defending our square count, we could ask:

“Show me what you’re seeing.”

That simple question transforms the interaction.

Recounting together reveals patterns that neither person noticed alone.

In the square puzzle, collaboration increases accuracy.

In life, it increases understanding.

Recounting requires:

- Patience

- Emotional regulation

- Tolerance for uncertainty

- Willingness to revise conclusions

These traits directly oppose narcissism.

Layers of Perception

Why do we miss squares in the first place?

Because perception is layered.

Your brain prioritizes:

- Large, obvious shapes.

- Familiar patterns.

- Efficient interpretations.

It deprioritizes:

- Subtle combinations.

- Unfamiliar configurations.

- Time-consuming analysis.

The same hierarchy applies socially.

We see:

- What confirms our beliefs.

- What fits our identity.

- What aligns with our group.

We miss:

- Contradictions.

- Nuance.

- Overlapping truths.

The grid is always more complex than it first appears.

Are Most People Narcissists?

If narcissism means chronic grandiosity and lack of empathy — no.

If narcissism means self-centered perception, defensive certainty, and overconfidence in our own grid — often, yes.

But this realization is not an accusation.

It’s an opportunity.

Awareness of bias is the first step toward expanding perspective.

The square puzzle is a gentle reminder that our first answer is rarely the final one.

From Narcissism to Curiosity

The opposite of narcissism is not self-doubt.

It’s curiosity.

Curiosity says:

- “What did I miss?”

- “How did you get that number?”

- “Let’s walk through it slowly.”

Curiosity keeps the grid open.

It transforms disagreement from threat to exploration.

It allows identity to remain flexible rather than brittle.

Counting Together

Imagine a culture where people approached disagreement the way good mathematicians approach puzzles:

Collaboratively.

Meticulously.

Without ego investment in the outcome.

The goal would not be to win.

The goal would be to see more.

That shift alone could reduce polarization, improve relationships, and deepen self-awareness.

Because the real problem isn’t that we miscount.

It’s that we defend our miscount as if it defines us.

The Final Square

Even now, reading this, you might think:

“I’m not like that. I question myself.”

Maybe you do.

But notice how quickly the mind exempts itself.

That reflex — the quiet assumption that this critique applies to others more than to you — is itself a hidden square.

The puzzle continues.

A Practical Experiment

Next time you find yourself in disagreement:

- Pause before responding.

- Notice the urge to defend.

- Ask the other person to explain their perspective.

- Look for one element you may have overlooked.

You might still disagree.

But you will have expanded your grid.

And expansion reduces narcissism.

The Grid Is Bigger Than You Think

“Most people are narcissists” sounds harsh.

But perhaps it’s more accurate to say:

Most people are incomplete counters.

We see what stands out.

We defend what we see.

We assume it’s everything.

The square puzzle is a metaphor for life’s complexity.

The visible shapes are never the whole story.

There are always hidden configurations, overlapping truths, and composite realities waiting to be noticed.

The question is not whether you miscounted.

You probably did.

The question is whether you’re willing to count again.

And maybe — this time — count together.